A recent guide from the NHBC Foundation provides an intriguing insight into the making of modern housing. Professional Builder’s Lee Jones reports.

In the public imagination the Victorian era is often characterised by the grinding Dickensian poverty of our capital’s slum-filled streets. Class and the contrasts between rich and poor were at their most manifest in the disparities in the quality of housing, but it is also true to say that our frock-coated forbears did much to lay the foundations for modern building standards.

![]() Breakthroughs in mains sewers, flushing WCs and waste collections, for instance, would save countless lives by eliminating the outbreaks of cholera that frequently plagued our urban centres.

Breakthroughs in mains sewers, flushing WCs and waste collections, for instance, would save countless lives by eliminating the outbreaks of cholera that frequently plagued our urban centres.

This was a time of huge social change, typified by a population explosion from 11 million in 1800 to 32 million in 1900 and overcrowded housing was one inevitable consequence. It was these pressures that drove social reformers to implement the Public Health Act of 1875 which required local authorities to adhere to Building Regulations – and for houses to be self-contained units with their own sanitation and water.

Moreover, initiatives like Henry Roberts’ Model Home, examples of which survive to this day on Streatham Street in London, were designed to give workers a more spacious living area. By the middle of the nineteenth century separate dining rooms had become commonplace, with the parlour or drawing room now reserved for relaxation, and running water would become a feature of the late nineteenth century bathroom.

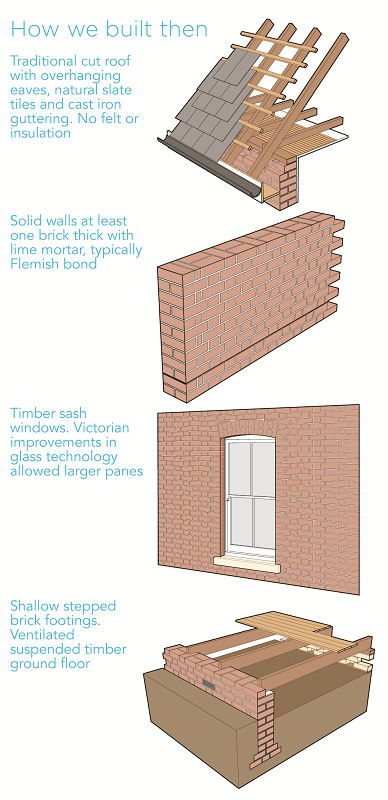

Any tradesman who has ever been involved in the repair or improvement of the vast stock of Victorian and Edwardian houses still standing will know that building techniques were very different from today. Traditional cut roofs with overhanging eaves, natural slate tiles and cast iron guttering were in evidence, but none of the modern insulation demanded of our more energy conscious 21st century living.

The emergence of the railways allowed for the rapid movement of people around the country, but at the same time also facilitated the transport of mass-produced building materials, allowing developers to build quicker and more efficiently – but that was far from being the only technological advance.

Thanks to Victorian improvements in glass making, the timber sash windows so typical of properties of the period were given much larger panes than would previously have been possible, allowing more natural light into properties that, in the absence of electricity, would still have been gloomy to modern eyes.

Thanks to Victorian improvements in glass making, the timber sash windows so typical of properties of the period were given much larger panes than would previously have been possible, allowing more natural light into properties that, in the absence of electricity, would still have been gloomy to modern eyes.

Cavity wall construction did not gain widespread use until after the First World War. Instead, the 19th century bricklayer would have been building a solid wall construction, at least one brick thick with lime mortar in a Flemish bond. Moreover, shallow-stepped brick footings would have seen a ventilated suspended timber ground floor above.

The best quality Victorian era homes were built to address issues of dampness, poor indoor air quality and sanitation, but standards in other areas were far removed from what we can expect today. The stringent health and safety guidelines that apply to building materials in the modern world, for instance, are in contrast to the Victorian era, when paints and varnishes would routinely contain highly toxic materials, such as arsenic and lead.

Similarly, as we strive for ever more energy efficient buildings there is a new focus on how our increasingly airtight properties are ventilated – whereas the chimneys and loosely fitting windows of the Victorian home would have provided all the ventilation (and uncomfortable draughts) that would ever be needed.

At the beginning of Queen Victoria’s long reign, homes built for poorly paid industrial workers were often cramped back-to-backs, built in densities approaching 250 houses per hectare, and were places where diseases like tuberculosis found fertile breeding grounds.

As the Nineteenth Century gave way to the Twentieth, however, improvements in every class of home were beginning to emerge – a trend that is at its most conspicuous in the ‘model village’ philanthropic housebuilding programmes of which Bournville in Birmingham was an example.

The poor health and low fitness of many of the First World War’s volunteer recruits was to accelerate the pace of change, and in the next issue of Professional Builder we will explore the ‘homes for heroes’ initiative and the profound impact the two great conflicts of the Twentieth Century have had on our house building practices.

For further information on the NHBC Foundation visit www.nhbcfoundation.org